The first of a series from the Wealthy Nation Healthy Nation paper edited by Malcolm Offord

This chapter was by Dr Gerard Lyons

SINCE THE 2008 global financial crisis, Scotland’s trend rate of growth has slowed significantly. From devolution until that crisis, growth was a healthy 2.2 per cent; since 2008, average growth has been just over 0.7 per cent.

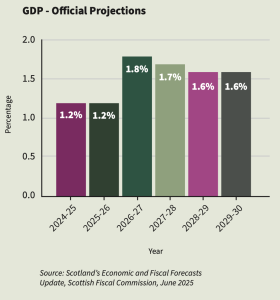

Official growth forecasts from the Scottish Fiscal Commission (SFC) expect modest growth (1.2 per cent) in the next couple of years, before rising to around 1.66 per cent over the remainder of the decade. These forecasts lean on higher migration and population growth. If, as seems likely, these growth forecasts prove optimistic then the fiscal projections built on them will be vulnerable.

How we got here

Since devolution, Scotland has seen a steady stream of economic plans. Early Labour–Liberal Democrat coalitions stressed market forces, skills and innovation, later adding sustainable development and social inclusion. The SNP’s 2007 strategy flirted with low-tax competitiveness before pivoting, post-crisis, towards a low-carbon economy and inequality reduction. By 2015, the focus had shifted further, embedding social objectives and the idea of ‘Fair Work,’ culminating in the 2022 National Strategy for Economic Transformation, which enshrines a ‘wellbeing economy’ that gives environmental and social outcomes equal weight to growth.

Over time, economic policy has thus moved away from Scotland’s historic strengths in enterprise and competitiveness towards state-backed social and environmental priorities, leaving the policy landscape cluttered with too many plans, too much bureaucratic control and too little focus on what genuinely drives growth.

How we get out of it

Scotland has a problem, and a clear task: rein in public spending to arrest a worsening fiscal position and pursue a pro-growth strategy that creates the conditions for private-sector-led growth, with enterprise once again the true driver. Without this shift, prosperity will erode.

Strengthening the economic foundation

Success will come from focusing on private enterprise as the driver of growth. Scotland needs three foundations to its economic agenda.

Fiscal discipline

The alarm bells should already be ringing about Scotland’s fiscal position. It is poor and looks set to deteriorate further. Public spending is not under control. Total public expenditure per person in Scotland is £21,192, versus £18,523 in the UK. Public spending increased to £117.6 billion in 2024/25, to a historically high level of 52 per cent of GDP. Excluding the North Sea, this ratio of spending is even higher, at 55.4 per cent as a share of onshore GDP.

Reforming the Barnett Formula in Scotland would bring economic gains. Resetting the block grant baseline and stopping off-formula top-ups would curb the persistence of higher per-capita spending. It would also make the system more transparent and strengthen accountability in Scotland, as Holyrood would bear clearer responsibility for the taxes it raises and the spending decisions it makes.

Supply-side agenda

The supply-side agenda is central: encouraging investment, innovation, infrastructure and incentives within a predictable regulatory and tax environment. Taxes should be simple and competitive, used as a lever to support growth rather than just raise revenue. While low taxes alone cannot deliver success, higher taxes weaken incentives and competitiveness, especially in sectors which need to be acutely aware of their international competitive position such as energy and finance.

Achieving strong economic growth is not possible if energy costs stay high. As one of the most important input costs across all sectors, energy must be at a competitive price. The focus should therefore be on energy addition, not energy substitution, as it is in many other countries that are also moving to renewables. The economic theory is that as the cost of renewables falls and technology advances including storage allow their reliability to improve, they will displace fossil fuels, eventually substituting for them. By contrast, the UK is moving towards substitution now.

Stability and finance

Monetary policy can often be overlooked in a focus on Scotland’s economy, but it shouldn’t be. There is a strong case for a change in the make-up at the Bank of England to give recognition to Scotland; appointing a Deputy Governor with explicit responsibility for Scotland, including oversight of its financial sector. This would reflect Scotland’s economic weight, improve representation in decision-making and give due recognition to Edinburgh’s role as a financial centre.

Conclusion

Fiscal discipline, a pro-business supply-side agenda and senior representation at the Bank of England are all essential if Scotland is to improve its policymaking and economic outlook. Overall, with more policy levers in its hands, Holyrood must move away from a top-down, centralised approach and foster local and individual initiative as the only route to lasting prosperity. Scotland needs to recreate a culture of enterprise and entrepreneurship.

Established in 2006, ThinkScotland is not for profit (it makes a loss) and relies on donations to continue publishing our wide range of opinions – you can follow us on X here – like and comment on facebook here and support ThinkScotland by making a donation here.

For the full paper visit Wealthy Nation Healthy Nation.

Dr Gerard Lyons has been described by The Times as “one of the most influential analysts of the global economy”, with over thirty years of experience in the City and public policy.