Racism and religious status assertion is worthy of investigation

THE ULTIMATE in status differentiation is the slave relationship. The slave has no agency, while the slave-owner has full agency for two. Leaving aside the special case of contract slavery, the general point about enslavement is that it reduces human freedom to the point where only death can exceed it in terms of general freedom reduction.

The anti-slavery movement is one of the very, very few good causes which the sane majority in civilised countries almost unanimously supports. The mystery for most people is that we are told the worst slavers were the Europeans who transported slaves from Africa to America for three hundred years when in fact slavery in the Islamic world has lasted since the time of the Prophet, which was fourteen hundred years ago. Over the piece, many more people were enslaved by Arabs and Turks than by Europeans. So why have we heard so little about Islamic slaving?

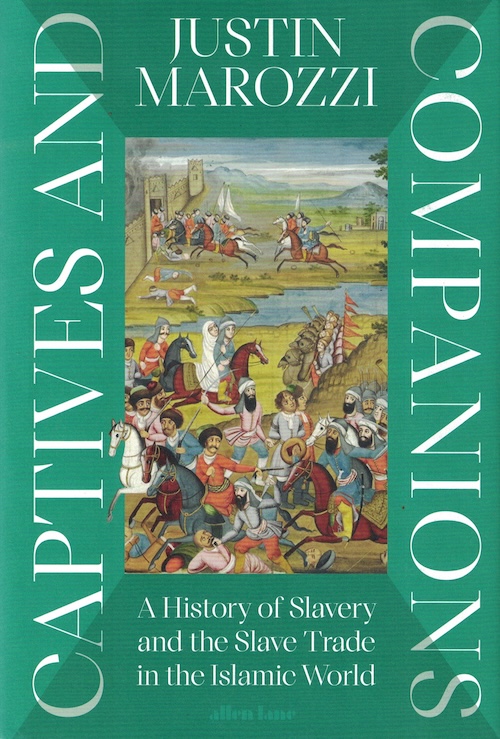

I cannot answer that question, but I can point to an excellent book which tells the story: Captives and Companions: a History of Slavery and the Slave Trade in the Islamic World, by Justin Marozzi. Published in July this year, it could hardly be more up to date. The author is an experienced Islamologist and traveller in Arab lands. Marozzi’s base is the University of Buckingham where he is “Senior Research Fellow in Journalism and the Popular Understanding of History.” For myself, I never knew that there was any significant popular understanding of history—otherwise how could the slavery issue have become so distorted in the public mind?

Enslavement is coeval with warfare. Later, it began after to seem silly to kill all the people you had defeated; better to enslave them and got some work done. So captives were sent into the fields or galleys and women into either the kitchen or the bedroom. Young boys were trained for service in the victors’ army in order to provide their masters with the means to continue their and their families’ subjection. The entire process was founded on contempt for “speaking property”.

Enslavement is coeval with warfare. Later, it began after to seem silly to kill all the people you had defeated; better to enslave them and got some work done. So captives were sent into the fields or galleys and women into either the kitchen or the bedroom. Young boys were trained for service in the victors’ army in order to provide their masters with the means to continue their and their families’ subjection. The entire process was founded on contempt for “speaking property”.

In the Arab world, this contempt was expressed in racism. Talking of the present, Marozzi says about Libya, for example: “I already knew from decades working and travelling in the country that Libyans were racist towards people with darker skin.” (p. 52) He adds that this was a result of “Libya’s history as a major centre of the desert slave trade.” But the present is racist too. “If you looked carefully enough at the 2011 revolution, the racism was there to see.”

A militia man in Tripoli explained to him: “Libyans don’t like people with dark skin.” (p. 53) “In 2000, anti-immigrant riots targeting workers in Libya from Ghana, Cameroon, Niger, Chad, Nigeria and Burkino Faso broke out and dozens were killed.” Marozzi himself discovered slave markets in which Africans were bought and sold “in secret auctions across Libya”. Likewise, some CNN journalists found “at least nine slave markets operating across the country.” Men would go for about $400 each. Traditionally in Islamic society, Marozzi tells us, “white girls were purchased on the whole for sexual services in the harem and black girls bought for domestic duties.” (p. 306)

Marozzi also tells us that Morocco “is a country ‘defined by colour lines’.” (p. 245) Black skin brought “shame” on the family. Whites were higher-end booty. In the early eighteenth century, Sultan Moulay Ismail of Morocco is said to have captured 25,000 white people and 221,320 black people “on the grounds of their skin colour alone, no matter how many of them were free Muslims and therefore protected from enslavement.” (p. 246)

In Turkey: slavery has disappeared but “prejudice and discrimination against the descendants of African slaves has not.” (p. 330) Such people “pray their children will not turn out so black” They are called Zenci, “a derogatory word which, like the Arab Zanj, is an approximate equivalent to the word Negro. Afro-Turks are often casually called ‘Arabs’ as well, a term Turks have traditionally used for people with darker skin. ‘We call ourselves Arab, too,’ Ahmet said: ‘It is better than “African”, which has such bad connotations – when people think of Africans they think of cannibalism and backwardness.’”

That was written by Mustafa Olpak. Ahmet was his grandfather, who had been captured in Kenya, offered for sale in Crete, bought by a Turk and put to work on a farm in Anatolia. He told his life story in Kenya-Crete-Istanbul: Human Biographies from the Slave Coast (published in French in 2006).

In the Nile valley, Marozzi says, Nubi (Nubians) are “white” while Sudani (Sudanese) are black and Sudan is “the land of the blacks, referring to all sub-Saharan territories in general.” (p. 333) But “the northern Arab Sudanese do not consider themselves black, reserving that pejorative term for their dark skinned Sudanese and South Sudanese compatriots, in addition to Africans from further afield whom for centuries they enslaved.” (p. 333) The Ottoman Empire, based in Constantinople, conquered Sudan in 1821, after which “women enslaved for sexual services were a staple of those who could afford them.” But if you could not, you could follow “a group of religious dignitaries in Khujalab, in what is today northern Khartoum, [who] clubbed together to buy a woman in common.” (p. 336) That did not end well as the oldest was given first dibs and he got the woman pregnant which rendered her unserviceable for the others, who then proceeded to sue over their loss of their female time-share.

Marozzi goes on to say: “Ancestry, in particular, was everything in Sudan. To be a brown Muslim Arab was to be free. To be a black non-Muslim African was to be a slave…. These stark racial views, deeply held by the Arab population, continue in much of Sudan today.” (p. 336) Slaves were classed as livestock and, as such, were not buried as that cost money. Instead, they were left outside for scavenging animals to dispose of. In nineteenth century Sudan, Marozzi says, “pale-skinned, northern Sudanese Arab Muslims looked upon their dark-skinned southern Sudanese pagan countrymen with the same sort of racist contempt Arab writers… had exhibited a thousand years earlier.” (p. 340)

The fact that slavery was formally outlawed in the Sudan in 1924 was entirely due to the British Empire which took fuller control of the area a decade after General George Gordon, the Victorian hero whom Lytton Strachey deprecated in Eminent Victorians, was butchered by Islamists in Khartoum in 1885. He was waiting for the British army to come to his rescue, but the Mahdi, a religious fanatic who declared that he had come to purify Islam, got there first with a horde of vengeful cutthroats. Gordon’s death was only one of several thousand people in the city who were similarly butchered by the Mahdi’s forces. Their main aim was to restore slavery which the British occupiers had tried to suppress.

The Mahdists succeeded in wrecking Khartoum so comprehensively that the capital of their state was moved to Omdurman. There, in 1898, the British army caught up with the Mahdists. Eight thousand British (including a young Winston Churchill who wrote about the experience in The River War), plus 13,000 Egyptian troops under British command, dealt the 52,000-strong Mahdi army such a shattering blow that it never recovered. Twelve thousand Mahdists were killed for a loss of 47 British and Egyptians, who also had a couple of hundred wounded, against 18,000 Mahdists wounded and taken prisoner.

Arguably, the application of that level of violence was the only practicable way of destroying the power of a fanatically religious slaver. Since the Koran permits the enslavement of non-Muslims, this would seem to be a necessary measure of self-defence by “kafirs” (unbelievers), as well as a proportionate way of defending light-skinned women and dark-skinned men from the contempt and violence of mobs of vicious barbarians.

A similar process of liberation was set in train in many of Britain’s African possessions. It is to the credit of the British Empire that it did so much to liberate Africa from Islamic, mainly Arab, slavery. The French Empire performed a similar role, though in a smaller area, starting with Algeria after the fall of Louis Philippe in 1848. The withdrawal of imperial Europe from what was once seen as “the Dark Continent” has allowed chattel slavery to re-emerge from the sewers of the racist mind.

Marozzi (pictured left) quotes the Global Slavery Index which lists the top ten countries in the world with the “highest prevalence of slavery” (p. 409). Apart from Russia and North Korea, they are all Muslim countries: Eritrea, Mauritania, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Tajikistan, United Arab Emirates, Afghanistan and Kuwait. That omits Sudan, of which Marozzi writes: “When the country split in 2011, it was estimated that over 35,000 South Sudanese remained enslaved in Sudan.” (p. 353)

In 1981, Mauritania became the last country in the world to make slavery illegal. However, “Here hereditary racialised slavery, despite its formal abolition, continues.” (p. 407) It is in this connection that Marozzi makes one the most important points about modern life world-wide. “When slavery was first criminalised in Mauritania in 2007, then again in 2015, it was a tacit and reluctant admission, from a government which had long denied that slavery existed in the country, both that the practice continued and that up to that point there had been no sanctions against slave owners.” (p. 407) But why would a government in effect allow slaving to continue after passing two laws to ban it?

The reason is given over the page: “The biggest slave owners are those in government. There’s no political will to end it.” (p. 408) Bureaucrats are the same world-wide: secretive, private nest-featherers looting public resources they were employed to steward honestly.

The next authority to turn his or her mind to the issue of slavery might care to address Mitchell’s Theory of Political Emancipation. Empires tend to be resisted by native leaders in the name of anti-colonialism. Most of such leaders are either bureaucrats or status-driven military commanders. They are the ones who usually benefit most from independence. As in Scotland today, local control gave many African leaders—think Robert Mugabe—and their clients the opportunity to loot their country without supervision from outside, in this case Imperial, authorities.

It follows that most of those who protest against imperialism are those who are closest in spirit to the slave-owning bureaucracy of modern Mauritania which conceals barbarity behind a virtuous façade of ex-underdog liberation. So the rule should be: Never trust the life of a fellow human being to a bureaucrat, ever!

Perhaps it would be best to leave the last word to the slavers. Marozzi says that when the Janjaweed militias attacked the inhabitants of Darfur in 2003, they “would enter the village of an African tribe, kill all the men and rape the women, mocking them afterwards with age-old racial slur: ‘You should celebrate, you slave. You are going to give birth to an Arab.” (p. 353)

Established in 2006, ThinkScotland is not for profit (it makes a loss) and relies on donations to continue publishing our wide range of opinions – you can follow us on X here – like and comment on facebook here and support ThinkScotland by making a donation here.

Photo of the painting ‘The Slave Market’ (1910) by Otto Pilny – Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=57412164