Cecil Rhodes and the question of who stole Zimbabwe from whom

READING this new biography of the great imperialist, Cecil Rhodes, provokes reflection on landownership rights amongst people who have no general concept of ownership beyond cattle and wives. Rhodes is a controversial figure today, due to his alleged racism and belief in “white supremacy”. The problem is that Rhodes was no more racist than most of his contemporaries, and much less than some. As far as white supremacy is concerned, he lived in an age when European civilisation worldwide was supreme. Rhodes was a man of his time. Who isn’t?

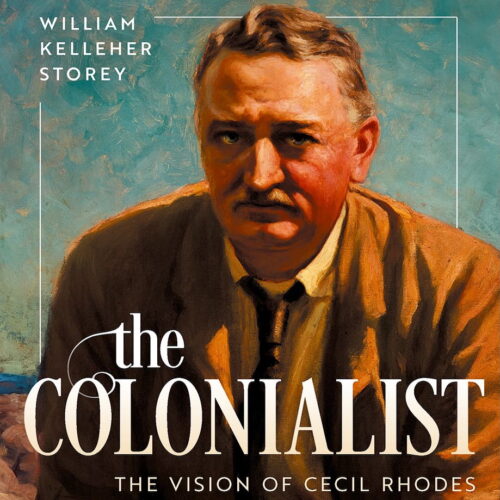

In The Colonialist: the Vision of Cecil Rhodes, William Kelleher Storey, of Millsaps College in Mississippi, has thoroughly researched the life of Rhodes and clearly explained it. Unfortunately, he is less thorough on the context. It is unfair to judge a man born nearly two centuries ago by the standards of 2025. Moreover, Prof. Storey’s acknowledgements give the impression that he studied documents only and did not get the dust of southern Africa on his boots. But even as far as the documentation is concerned, there is at least one important gap.

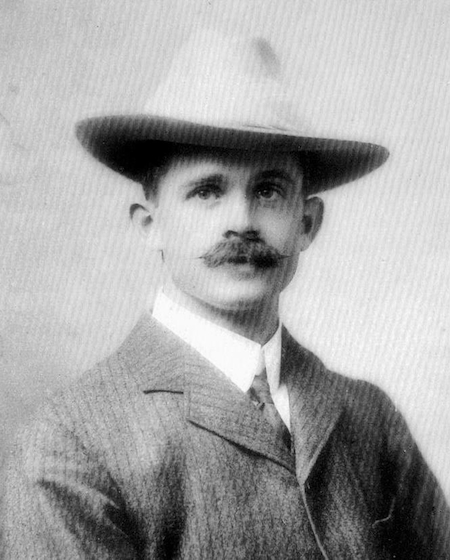

An important source for the final negotiations at Bulawayo which brought peace to Matabeleland was Rhodes’s private secretary, Philip Jourdan (below). He was an eyewitness who published his impressions in 1911, soon enough after the event to be considered contemporaneous. Yet Jourdan’s book, Cecil Rhodes – His Private Life by his Private Secretary, is not mentioned anywhere in Prof. Storey’s bibliography, despite the inclusion of such distantly-relevant titles as Boswell’s Life of Johnson.

However, Prof. Storey is fascinating on the subject of how Rhodes built up De Beers, Consolidated Goldfields and the British South Africa Company. There is less information on Rhodes’s political career, latterly as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony, except in the context of his tendency to mix public power with private, commercial ends in the style of, say, Standard Oil or Pierpoint Morgan’s railroad trusts, not to mention modern corporations and most of today’s Russian and Chinese “national champions”. That sort of “corruption” was not a purely British imperial problem, as many FDR-type imperialists like to pretend.

However, Prof. Storey is fascinating on the subject of how Rhodes built up De Beers, Consolidated Goldfields and the British South Africa Company. There is less information on Rhodes’s political career, latterly as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony, except in the context of his tendency to mix public power with private, commercial ends in the style of, say, Standard Oil or Pierpoint Morgan’s railroad trusts, not to mention modern corporations and most of today’s Russian and Chinese “national champions”. That sort of “corruption” was not a purely British imperial problem, as many FDR-type imperialists like to pretend.

Storey’s depiction of Rhodes’s public personality is of an exceptionally driven man who achieved in a quarter of a century what few other “great men” men could have achieved in several lifetimes. (He died aged 48.) He did nothing much else, all his waking hours, than devote himself to business, politics and the expansion of British influence and interests in southern Africa. Since he was educated at Oxford, and gave much of his wealth to the University to endow the Rhodes Scholarships, it seems to me entirely appropriate he has a memorial statue outside his old college there.

Rhodes was neither an unkind man, nor a dishonest one in personal dealings. He was well liked by his peers. The main interest in his life today concerns alleged “land theft” in southern Africa, especially the land of the Matabele (or Ndebele) tribe in what is today western Zimbabwe. Prof. Storey makes that allegation without discussing it which, given the gravity of the charge, is not very even-handed.

The founder of the tribe was Lobengula’s father, Mzilikazi, who fled from Zululand due to fear of the half-crazed, Pol Pot-like violence of Shaka, the controversial chief of the Zulus in the post-Napoleonic period. Mzilikaze first took his followers up from Zululand on the coast to the highveld in what was later to become the Transvaal. There, his impis murdered so many of the local tribespeople there that when the Boers trekked into the area in the 1830s and ’40s they thought the country was empty.

Under pressure from the Boers, the Matabele fled further north into what was later to be called Matabeleland, in the western half of modern Zimbabwe. By the time Rhodes and his associate, Charles Rudd, arrived at the tribal capital of Bulawayo in the late 1880s, seeking mining and farming concessions, the chief they found themselves dealing with was Mzilikazi’s son, Lobengula. He was as imperial, colonial and savage as his father. He had already pushed other tribes out of the land he had taken and reduced the neighbouring Shona people to tribute-paying vassals.

Lobengula’s warriors levied “taxes” in the form of cattle, which was the main store of wealth in pre-Europeanised southern Africa. If the Matabele met resistance to their policy of expropriation without compensation, they killed the men involved, enslaved the women and forcibly enrolled the male children in their own armies, rather as Mr Putin is doing today with kidnapped Ukrainian children in the occupied Donbas.

In promoting British expansion into the area, Rhodes was doing to the Matabele only what they had already done to the Transvaal tribes and the Mashona. Lobengula’s people had no ancient right to the land they occupied. As incomers in a pre-writing culture, they had no means of asserting title to an area other than by killing, enslaving or displacing the previous inhabitants. Bottom line: the Matabele had no more “right” to the land in question than Rhodes did.

Had the British not invaded the country, the Germans in neighbouring South-West Africa might well have done so. Hermann Göring’s father, Heinrich Ernst Göring, was Reichskommissar for the territory from 1885 to 1890. By then a brutally racist policy of what amounted to extermination of the Herero and Ovambo peoples had been set in train. It nearly worked. The country was depopulated and the blacks driven into the desert. The (pre-Nazi) Germans were closer in spirit to Mzilikazi than to Cecil Rhodes and his deal-makers, however slippery they were (and that was pretty slippery).

In the opposite direction, Portugal with its chaotic semi-military rule claimed much of eastern “Rhodesia”. The other European power in the vicinity was King Leopold of the Belgians who occupied the Congo. His was one of the most viciously cruel and racist regimes ever to befoul the earth, comparable to the Arab slave traders (whose history I shall be covering in my next review). Modern Zimbabweans ought to be grateful it was the British who colonised their land rather than the Germans or Belgians.

Despite that, the Matabele rose up against British administration in 1893-94. As always, they fought bravely and, against a scouting detachment on the Shangani river led by Major Allan Wilson (from Glen Urquhart), chivalrously. When 3,000 impis had killed every one of Wilson’s 34 troopers, who fought to the last bullet, the Matabele for once did not mutilate the corpses of their defeated opponents. Recognising their extreme bravery, they later said: “They were men of men, and their fathers were men before them.” (Not mentioned by Prof. Storey.)

The final negotiations were held in 1896 with Lobengula’s successor, Njube, after a second war in which the Matabele fell on, and killed, hundreds of individual settlers and their families, often on isolated individual farms. Instead of storming into Bulawayo swearing vengeance, as Lobengula or Mr Putin would most likely have done, Rhodes attended upon Njube, and waited patiently for him to come out of his “hiding place” to do business.

This was the century of “unequal treaties” in China, north America and elsewhere. Rhodes’s treaty with the Matabele was pretty unequal too. But it was not imposed by force. Neither did Rhodes empty the land of its previous inhabitants in the way Mzilikazi had done. There was no “trail of tears” such as the Cherokee nation had to endure at the hands of the US Army when they were evicted from Georgia (where even the US Supreme Court in Worcester v Georgia (1832) had said they had good title). The English wheeler-dealer preferred to rely on the civilised idea of contract rather than his primitive status as a conqueror.

After emerging from his hiding place, Njube was entertained by Rhodes for about a fortnight. The Chief then consented to send a messenger to his indunas [tribal elders] advising them to come out of their own “hiding places” to see the white men. Each chief usually stayed for a few days, then returned to talk the matter over with his people. As Philip Jourdan writes (but Storey ignores): “When in Mr Rhodes’s view the time was ripe a big Indaba [meeting of the chiefs] was arranged at which all the chiefs were present. Several heads of cattle and sheep were killed for the occasions. Two or three meetings were held, and eventually peace was concluded… [Rhodes] sat day after day throughout the heat of the day talking to the chiefs and cracking jokes with them, until we were tired to death of the sight of them. But his patience and perseverance gained him the day… Mr Rhodes’s physical strength and powers of endurance were phenomenal at this time.”

Rhodes’s aim was to eliminate routine violence and theft so that non-tribalists could settle on farms in the area and try to make the land more productive. The price of that was an end to the traditional life of the Matabele as that involved predatory theft on an organised basis as the main form of economic interaction. That logic was not peculiar to Africa (or Jacksonian America, for that matter). It was used by Enlightenment “improvers” in eighteenth century Scotland when thinking about Highlanders and their habit of stealing cattle from settled lowland farmers.

Both the Matabele and the Scottish clans were organised primarily for war, not wealth generation. The adult male population was under arms to facilitate cattle reiving and land “theft”. Such a way of life reduces economics to a question of forcible asset transfer, the ultimate zero-sum game in group relationships.

As in much of Highland Scotland in the early modern period, production in Matabeleland was the responsibility of the women, who had to plant, tend and mill the mealies, as well as to milk the cows, clean the hut, feed the men, chase the hippos out of the pumpkin beds, etc. The potential for productivity growth was close to nil. The result in both cases was a society which was so poor and technologically backward that it could not defend itself against invaders from richer, more advanced ones in which the state protected lawful contracts from predatory gangs.

The great imperialist had his faults, but Rhodes was, at bottom, a constructive individual who wanted to build an economy based on production rather than on systematic theft. That is the only sustainable approach to economic growth, as Putin’s corruptly militarised Russia or Swinney-Sturgeon’s slyly kleptocratic Scotland negatively demonstrate. Prof. Storey quotes a Matabele under-chief, Somabhulana, who made a gracious concession to superior status early in the series of meetings just described. “You came, you conquered,” he said. “The strongest takes the land. We accepted your rule. We lived under you. But not as dogs! If we are to be dogs it is better to be dead.” (p. 356)

Rhodes’s general position on race and economics was stated explicitly in 1898 when he was leader of the Progressives in the Cape parliament (he was no longer Prime Minster as a result of the Jameson Raid). The Party’s slogan was “Equal Rights for Civilised Men”. The question, of course, is what Rhodes meant by “civilised”. Prof. Storey quotes a note he wrote to his friend and biographer, Lewis Michell. “My motto is equal rights for every civilised man South of the Zambezi. What is a civilised man? A man whether white or black who has sufficient education to write his name, has some support, or works – in fact is not a slacker. C.J. Rhodes.” (p. 389)

That definition would rule out 90 per cent of the modern British bureaucracy and 99 per cent of the European one. Both are largely made up of predatory slackers superficially disguised as wokey public servants. So I think Rhodes was right.

It would seem the Matabele thought in positive terms about the great imperialist too. Enormous numbers of them attended his funeral, quite voluntarily, at World’s View in the Matopos in 1902. That included the Chief, Njube. He and his tribesmen recognised Rhodes as a quasi-kingly figure whose eternal presence among them would not disturb what they thought of as “the spirits of the hills”. Compliments in Africa do not go much higher than that.

Prof. Storey says of the event: “At the top of World’s View, the burial did not conclude with the traditional salute by a firing party. Ndebele leaders objected to the idea of such a noise, on the grounds that rifle shots might disturb the spirits of the nearby hills, where burial sites are located. Ndebele men were given the last word on Rhodes: they closed the ceremony with the royal tribute: ‘Bayete!’” (p. 406)

If you appreciated this article please share and follow us on Twitter here – and like and comment on facebook here. Help support ThinkScotland publishing these articles by making a donation here.