The euphoria of fear: On the loss of psyche in modern medicine

ANOTHER NIGHT, another shift. The corridor lights hum like old neon, and I catch my reflection in the crash-room window: white coat, hollow eyes, and the faintest hint of someone who once believed the system worked. The air tastes of disinfectant and unasked questions.

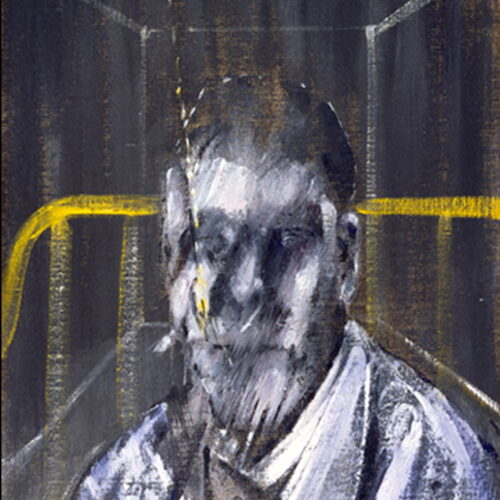

At 3 a.m., medicine feels less like science and more like theology that forgot its God. In the mirror looking back at me is a vision like ‘study for a portrait’ painted in 1952 by Francis Bacon (pictured).

Somewhere between resus and cubicle nine, I remember something a patient once said, “Doctor, I’m not mad or sick, I just don’t feel like me anymore.”

That line sits heavier than a cardiac arrest. Because how do you treat someone who has lost the bridge between body and mind — the psyche — when your training insists such a bridge doesn’t exist?

We doctors like to divide. It’s how we make the chaos bearable for us: mental versus physical, organic versus functional, acute versus chronic. It’s neat. It’s safe. It’s wrong. The more I see, the more I suspect that this tidy dualism has quietly unstitched us. We have built an empire of protocols and scanners, yet the people under our care — and the doctors themselves — are dissolving. Not because the science is bad, but because it’s incomplete.

When psyche left the consultation room, we mistook her absence for progress. We called it secularisation, evidence-based practice, professional maturity. In truth, it was an exorcism. The old tripartite model — body, mind, soul — was amputated, leaving two fragments to quarrel endlessly over the corpse of the third. We call it “integration,” but it’s just the absence of a truce between two egos who both think they’re in charge.

We fix bones and medicate thoughts, but no one asks what holds them together. Without psyche, neurology and psychiatry glare at each other across the ward like estranged siblings at a funeral, both pretending they weren’t raised by the same mother.

It’s not fashionable to say that in public. The system doesn’t like mysticism; it likes metrics. But what are we measuring if not the slow disintegration of the human being into data points? We speak of “mental health” as if the mind were a department that could file a complaint against the liver. We speak of “physical health” as though the heart did not quicken from shame, or the gut twist from grief.

And so the hospital becomes a machine that repairs the mechanical consequences of metaphysical neglect. We treat the debris of the unacknowledged soul.

The cruel joke is that the doctors suffer first.

The profession that denied psyche is haunted by her absence. Burnout, depression, cynicism — these are not diseases of overwork alone, but symptoms of metaphysical starvation. When all meaning collapses into measurable outcome, the healer becomes technician, the oath becomes policy, and fear masquerades as control.

Senior doctors, once apostles of vocation, harden into bureaucratic cynics. Compassion atrophies; cruelty creeps in. You can almost hear the bartender’s whisper: “White man’s burden, Doctor. What’ll it be?”

Jack Torrance sold his soul for bourbon; we sell ours for data compliance and rota gaps. The deal is the same — a little comfort in exchange for a little less of ourselves. And when the ledger runs dry, Lloyd still smiles and says, “Your credit’s fine, Doctor.” It always is, right up until the moment you realise the bar tab is your conscience.

Fear is the common currency here. Not the fear of death — we’ve grown immune to that — but the quieter terror of not even knowing who we are anymore. Fear of seeing the psyche reflected back and recognising her as the patient we abandoned. Yet there’s no euphoria quite like that fear, because in that moment of vertigo lies the first hint of reunion. To see the wound is to feel alive again.

Perhaps that is the beginning of integration — not another framework, not another “model of care,” but a re-acknowledgment that health is the harmony of what we have divided. Body, mind, and psyche are not domains but dialects of the same language. Medicine once spoke it fluently, before it forgot that biology without meaning is just plumbing.

Reintroducing psyche doesn’t mean turning hospitals into churches. It means remembering that science, stripped of interiority, becomes superstition of another kind — the superstition of material certainty. It means understanding that a person’s illness is never just in their brain or their blood but in their being, in how the world perceives them and how they perceive the world in return.

Without that, we treat only consequences. We keep the body alive while the person inside quietly disappears.

So here I am again, end of shift, knocking back another existential cocktail — equal parts caffeine, irony, and despair — and wondering what the hell happened to medicine. The monitors beep like slot machines, the corridor smells of antiseptic and resignation, and somewhere between the living and the dead, the psyche still waits for us to notice her.

Until then, we’ll keep knocking them back. One by one.

You set them up, and I’ll knock them down.

But somewhere in that ritual of futility, a thought lingers: maybe the real intoxication was never the bourbon or the data or the power — maybe it was simply the taste of having once known the soul.

Close your eyes.

Hear the wind and the cold of the sea against your feet.

Remember the last time you loved the world and, in that same instant, loved yourself.

Now see the small child you once were—bright, open, defenseless—and feel the quiet ache of how far you’ve drifted from him.

That ache is not cruelty; it is recognition. It is the psyche stirring in the dark.In that recognition lies fear—the most lucid of emotions.

It floods the body with light and tremor, a terrible euphoria that says: You are alive.

For a moment, the partitions between body and mind dissolve, and what was lost begins to return.We once had names for that sensation: spirit, soul, psyche.

Now we call it chemical, incidental, inconvenient.

But beneath every diagnosis, every protocol, the same wind moves—asking us to remember.

They don’t make that kind of awe anymore.

Perhaps we traded it for certainty. Perhaps that’s what secularism costs.

For when God exited medicine, Rumpelstiltskin took over and called itself Reason, that is the self-serving pacemaker of a human without a higher authority to orbit beneath.

Disintegrative Medicine has put Rumpelstiltskin in charge.

God, help us all.

Established in 2006, ThinkScotland is not for profit (it makes a loss) and relies on donations to continue publishing our wide range of opinions – you can follow us on X here – like and comment on facebook here and support ThinkScotland by making a donation here.

Photo of Study for a portrait by Francis Bacon courtesy of the estate of Francis Bacon – visit it at https://shop.francis-bacon.com/