JUST OVER five years ago, I brought out a book called ‘Scotland Now: A Warning to the World’.

I was chastised for the melodramatic title. Academics in particular disliked it. Far from undergoing a collective nervous breakdown, Scotland was emerging as a politically innovative place. I had no right to rain on the parade. But I stood my ground. Today it is consoling to see at least one well-known political scientist, who discouraged students from using my alarmist book in their essays, now endorsing in print some of my strictures on political nationalism.

I summed up the SNP midway through its stint in charge of the devolved institutions as a protest movement with a capable propaganda machine, masquerading as a party of government. Clever, often uninhibited, political agitation appealed to some of the more turbulent aspects of the Scottish psyche. As the sway of the established parties was fading, the mood of society, especially in post-industrial areas, was growing volatile. People were searching for a new moral paradigm, one with far fewer rules and obligations. The culture of work which had provided a stable underpinning for one of the world’s first industrial societies, was receding in importance. So was religion.

Fear of God and belief in an afterlife were declining as factors which checked some of the wilder human instincts. The numbers who increasingly feared nothing were no longer restrained by fear of community disapproval. Civic Scotland was decaying. Organisations representing local identities and interests were fading, replaced by campaigning groups and charities ready to offer obedience to the powerful in return for subsidies and other favours.

A brash and wily leader, Alex Salmond made egotism respectable. It was quite new for a leading politician in Scotland to do this. His appeal was to predominantly male working-class voters seeking fresh loyalties. The motivation shown by both himself and team (with Nicola Sturgeon already his heir-apparent when in her mid-30s) was impressive. Many new adherents hoped for limitless undefined change. But of course the shaking up of the political world and society was to result in the creation of a new establishment.

The culmination of the march to power came with the gifting of a referendum on independence to the SNP by British prime minister David Cameron. Social media proved to be an agitational tool of prime importance, firing up idealists as well as dragging into politics many with a militant approach to electioneering.

I was writing in the aftermath of the 2015 general election when, having won 57 of 59 Scottish seats, I expected the SNP to embark on a lengthy reign as a dominant force in Scotland. Building an achievement-orientated state was not on the cards, I predicted. Populism would triumph as the non-stop manufacture of grievances and ill-feeling against Westminster shaped the discourse of the SNP. Below the surface (and unreported by the media), an efficient distribution of favours was taking place. A client state was being created with billions supplied from the senior government in London making it possible.

Predictably, for a party intent on a power-grab runaway centralism became the order of the day. It made the Thatcher era seem like the Summer of Love in San Francisco. For those with eyes to see, it showed the disdain the SNP had for devolution along with the desire to create a weak parliamentary order where informal rules predominated.

I unavoidably upset some nationalists who inveighed against the book online for daring to compare the SNP with New Labour. Today a large subsection of Nationalists who believe they have been betrayed by a leadership, regularly use this comparison. Both parties of Blair and Sturgeon were and are obsessed with communications and spin, politicising large areas of public life previously removed from political warfare, launching ill-thought-out and often expensive experiments which backfire on them, getting entangled with international snake oil salesmen, and plunging into foreign adventures which generated growing unease among supporters and activists.

Sturgeon has no army behind her (thankfully) but foreign affairs has become almost as much of an obsession as it was for Blair. Most of her recent time in office has been absorbed with Brexit which arguably has not done anything for the independence cause she entered politics to accomplish. Out of office, she is unlikely to end up a well-paid advisor for dictators like Blair but it is hardly a secret that she is looking for a job in one of the international bureaucracies that are increasingly seeking to regulate the thought and action of billions of people across the planet.

What I failed to appreciate was the degree to which the SNP would get into serious difficulties as a result of squandering its credibility thanks to unwise and often highly dubious courses of action. It took a few years longer in the case of the SNP. But hubris has shortened the political lifespan of Sturgeon as surely as it did that of Blair before her.

The SNP assumed a new age had begun under it. 2015 was 1997 when the feeling was rife that the world was at Labour’s feet. It could devise the rules which the opposition would have to comply with. A blizzard of law-making would ensue. Much of it was designed to create a society, newly-engineered from the left, one that was receptive to ideological zealotry. To the credit of Scotland, the SNP’s bids to diminish human rights through criminalising football behaviour, and introducing laws on hate speech and the state supervision of children, has produced massive uproar and ignoble retreats have resulted.

The eruption of a feud between the pair of politicians who symbolised the prowess of both Labour and the SNP, is the most tantalising parallel. The Sturgeon-Salmond fight to the death was not on the horizon when my book was completed. The Blair-Brown quarrel had rumbled on right through the New Labour ascendancy. It was clearly highly debilitating and it might have served as a warning not to allow personality disputes to endanger the retention of power in the land.

But Sturgeon has been as susceptible to outwardly alluring foreign examples of progressive thinking as Blair was. What might be described as Salmond’s calvary as he faced marginalisation in the party, state investigation, a criminal trial for serious offences, and continued attacks on his character from his boss after he walked free from court, began at the same time the #MeToo movement succeeded in toppling powerful men guilty of sexual misconduct.

The determination of middle-class progressives from the media and the third sector (whose influence in the SNP surged under Sturgeon) to characterise Salmond as Scotland’s Harvey Weinstein was matched by his own determination not to go down in history saddled with such a terrible image.

A gaping split occurred over the alleged wrong done to Salmond by his successor and by the time both gave evidence to a parliamentary committee in Edinburgh in February 2021, it was regarded as perhaps the most serious crisis in the history of the SNP. Two camps opened up comprising people wedded to conflicting types of identity politics. There were the long-term adherents for whom territorial independence was the alpha and omega of the struggle for national self-determination – and there were a motley collection of self-confident social radicals who had advanced within the party machine run by Sturgeon’s husband Peter Murrell. They saw personal liberation as the imperative without which a successful exit from the United Kingdom would leave oppressive power structures and mentalities untouched, resulting in sham independence.

I was already aware of the radicalisation of a portion of the young and of women, particularly from the urban middle class and I presumed the SNP would be able to act as ‘a big tent’ party reconciling these tendencies. After all, other durable parties had done so, such as India’s Congress Party and the US Democratic Party. But remarkably, Sturgeon failed to carry off the balancing act and perhaps stranger still, she did not seem that bothered about trying.

She backed the social radicals, identifying with their most outspoken element, militants in the transexual movement who wish to occupy women’s spaces by self-declaring as women. In 2017 she had been identifying with the #MeToo movement designed to cut powerful importunate men down to size. But by 2021 she had thrown her mantle around a group whom numerous feminists believed had been politicised by men who endangered the safety and rights of women by refusing to recognise long-established gender boundaries. This party crisis has shown Sturgeon to be a stubborn figure who retreats with difficulty. Last Friday a Hate Crimes Bill was passed into law which offered no protection to women prepared to offer resistance to men being allowed to pose as them by applying self-declaration. Instead, they were the ones afforded protection under this new law.

National movements pushing a reluctant country towards statehood have learned not to be sidetracked by such sectional issues. It is incredible that the SNP has thrown aside such elementary prudence. After Sarah Everard’s murder last week the SNP MP for Livingstone Hannah Bardell supported online the idea of a curfew for men after 6pm only to be rebuked by Councillor Chris McEleny who pointed out that her proposal would prevent male workers on nightshift being able to turn up for their jobs.

Increasing numbers of nationalists no longer conceal their belief that the leader of the SNP has ceased to be pro-actively engaged in fighting for independence. A wave of resignations from the SNP has occurred, some leaving quietly others noisily denouncing the claque of mediocrities, careerists and social extremists who prevail in the party’s deliberative bodies and candidate selection processes.

Opposition to the Hate Crime Bill was perhaps stronger among grassroots SNP supporters than in any other party. It may result in former members of many years standing deciding to vote in a way best designed to deprive Sturgeon of power in elections due on 6 May. A segment of the party is disengaged and demoralised, amounting to at least several tens of thousands of people. It now assails its leader far more forcefully than nationalists attacked standard-bearers of the union like Alistair Darling and Jim Murphy in 2014.

Even if Sturgeon quells the rebellion and is able to remain in charge, it is clear the sands have shifted in the SNP. Those in the ascendancy are bound up with niche issues which they are trying to impose on the rest of society through the law, education, and an often-compliant media.

Some wiser heads among unionists who are aware that independence may well remain an unquenchable ambition for perhaps as many as 40 per cent of Scots quietly say they would like to see Sturgeon’s SNP limp back into government, perhaps more than ever dependent on the Green Party. She will remain the head of a divided and demoralised party and even if she makes some gesture towards challenging Westminster’s writ in Scotland, it is unlikely to be done with much conviction or dexterity.

The good news for this British-minded writer is that the limitations of political nationalism in Scotland have been exposed earlier than I had assumed they would. The impact of endless propaganda around Britain quitting the EU or a leader-centred fight against Covid largely directed from television studios, has been far less profound than I supposed. If it focuses on independence, an SNP election campaign will be seen as bogus by many given the scale of internal divisions. Meanwhile, the ideas of opposition parties on how to fix some of the problems which the SNP has allowed to reach crisis levels, will probably be given a more responsive hearing than at any time since before the referendum age got underway in 2011.

The bad news is that the politics and governance of much of the West is in a shambles. So any warnings about dark happenings in Scotland will probably largely fall on deaf ears. Clearly, Woke ideas at war with common sense have produced a stark levelling effect.

If you enjoyed this article please share and follow us on Twitter here – and like and comment on facebook here.

Tom Gallagher is Emeritus Professor of Politics at the University of Bradford. He is the author of Theft of a Nation: Romania Since Communism, Hurst publishers 2005. His latest book is Salazar, the Dictator Who Refused to Die, Hurst Publishers 2020 (available here) and his twitter account is @cultfree54

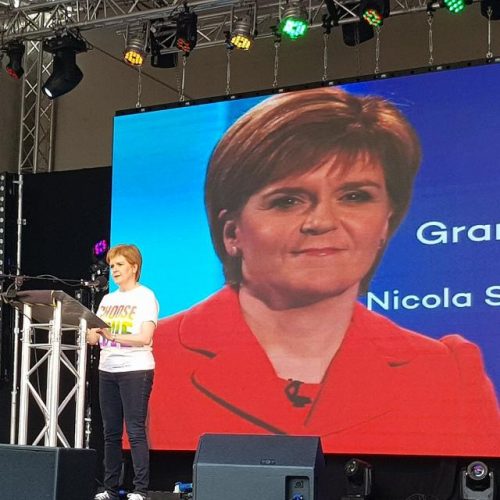

Photo of First Minister Nicola Sturgeon talking as Grand Marshall at the Glasgow Pride 2018 festival by Delphine Dallison – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=70872999