AS SHE FACES a showdown this week with the man whom she bizarrely turned on after he placed her on the path to political stardom, Nicola Sturgeon is fighting for survival on multiple fronts.

She is trying to get an election out-of-the-way as quickly as possible in the hope it will give her the authority to say, ‘Okay folks, plenty of you are saying I may have broken the ministerial code in the way allegations over Alex Salmond were handled. But so what? The people have spoken. Enough of them still love me. I go on regardless of what others might think.’

Beleaguered, she dominates the small Scottish political stage because no other contenders for office are allowed much political oxygen. BBC Scotland allows her a personalised daily show, supposedly to cover a complex medical emergency, one in which she strays regularly into political polemics. Meanwhile the new BBC Scotland politics editor Glenn Campbell is mired in controversy because he gave a soft touch interview to one of the complainants in the Salmond affair ? His ex-BBC colleague Andrew Neil, on the verge of launching a competitor channel GB news, says he has major questions to answer for having done so.

Sturgeon will have her regular BBC soapbox right up until voting day for the Holyrood elections. But other politicians will not be allowed their own street corner soap boxes. Campaigning will be heavily restricted by law. It means there will be no in-person electioneering which even fake democracies in the Third World often still allow. While even pizza sellers can deliver leaflets for their wares, parties will be prevented from putting election literature through letterboxes.

An embattled but shrill SNP leader promises that a victory for her party will make independence a live issue in UK politics. But she knows (and is probably unfazed by the fact) that an election fought on such a questionable basis, is unlikely to give her a mandate for a further bash at breaking up the United Kingdom.

Her priority is not delivering Indy or breaking the pandemic but personal survival. She is far less concerned about the reports that land on her desks from health advisers or by the latest pro-Union moves from London, than with seeking to avoid being consumed by the fall-out arising from a failed bid to dispose of her former boss.

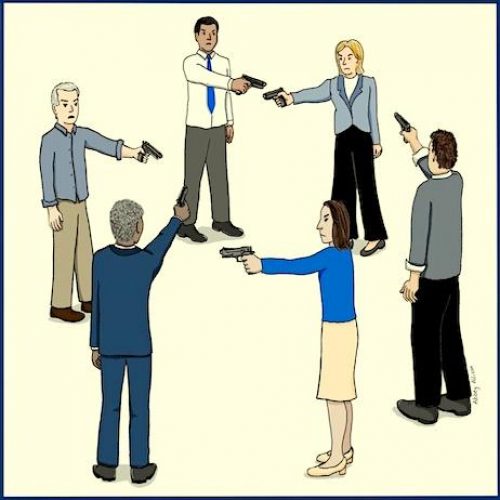

The longer she lasts the more it seems that debilitating factionalism will be her main political legacy. Scotland isn’t destined to be a New Zealand or Estonia of the future when politically at least it increasingly resembles a Belfast or Beirut, hopelessly mired in factional strife. She is a warhorse whose turf is being encroached upon not by the long-term enemies of her movement but by dissidents and former allies who view her as a usurper. They despise her for so plainly putting her own career before (as they see it) party interests and the cherished goal of establishing a Scottish independent state.

It may only be in the fullness of time that the silence of most of the SNP’s 108 parliamentarians as Sturgeon and her enemies slug it out will be seen as a harsh verdict on the ability of the party to confront and conquer challenges. If it cannot put its own house in order how can it plausibly claim to run a country, especially when it has failed to cure any of Scotland’s ills despite all the free money flowing from hated London?

The battles in the SNP are being largely fought out in the media. Ex-journalists now working for the SNP and those still in the trade, who take different sides in the undeclared civil war, are the main protagonists. It is an unflattering comment on public life in Scotland that a profession which is only being kept alive by large injections of public cash to spin doctor journalists and low circulation publications, is so central to political developments.

Silencing critics who have high profile media spots is an increasingly urgent priority for Sturgeon and her allies. Robin McAlpine, the prolific commentator and founder of the influential Indy platform Commonweal was toppled by colleagues after his criticism of Sturgeon’s conduct at the helm of party and state grew increasingly forceful. Next Joanna Cherry MP was peremptorily sacked as the SNP’s justice and constitutional affairs spokeswoman at Westminster after taking issue with her leader’s endorsement of radical trans activists.

Arguably, a far bigger thorn in her side, is Stuart Campbell who has run the pro-independence Wings over Scotland site for a decade. He is easily disparaged as a former computer games programmer operating from Bath, Somerset. But he is far better-informed about doings within the SNP and the wider Yes (pro-Indy) movement than most journalists. He wields a ferocious pen and has a mordant and scabrous wit. His ferocious invective was directed against Unionists for years but it is proving far more potent when it is directed at leading people in the movement whom he views as apostates if not outright traitors.

Neil Mackay, the former editor of the now defunct Sunday Herald and now a freelance contributor to the surviving daily Herald, belongs to a group of journalists who have long groaned about the ability of Campbell to become an independent force in nationalist journalism. They watch helplessly at Wings’ repeated ability to raise funds through crowd-funding efforts while their own careers languish due to the collapse in revenue for the titles that they write for. Mackay has arguably been courageous for forcefully challenging Campbell after dark insinuations about his ultimate political loyalties were penned in a Wings article. In a riposte Mackay urged that the party take action against those within its ranks who consorted with Wings in different ways.

His appeal was addressed to the top but I thought at the time that it would be ill-advised for Sturgeon to move against Wings directly. Campbell had been among the first in the world of Nationalist activism to conclude that Alex Salmond was being framed and by taking aim at him, she risked being seen as trying to take out one of the most steadfast allies of her foe at a most delicate point. Moreover, to many prominent figures in the SNP admire Wings for its ‘consciousness-raising’ efforts down the years and for acting as a vigilant guard against diluting the party’s core objectives. One of them, the former justice minister Kenny MacAskill had an article in Campbell’s online platform as recently as 19 February.

But it seems I was wrong. Nicola Sturgeon participated at a meeting of her party’s ruling body on Saturday at which calls for forceful action were made against those who gave oxygen to Wings. Possibly the most important outcome was the decision to adopt a new definition for transphobia, which has stoked fears that members would face expulsionfor describing certain trans-sexuals as biological men. Sturgeon spoke at length at the online meeting of the national executive committee and the motion was passed thanks to the unelected affiliate groups who make up 30 per cent of the NEC. With a firm Sturgeon ally, ex-human resources manager and now Westminster MP Sandra Osborne presiding over the NEC, it appears none of the protagonists are keen to secure a compromise as the party faces into an unpredictable election.

Sadly for some, as journalists and bloggers brawl and battlelines around identity politics harden within the SNP, it has not been the finest hour for Scottish civil society. Perhaps Scotland’s most visible civic luminary Darren McGarvey, a campaigner on drugs issues, rapper and award-winning author, let fly in a furious diatribe on the evening of 17 February when he urged that Stuart Campbell be paid an unfriendly visit and that he ought to ‘wake up next to a horse’s head.’

McGarvey is one of those social activists, like Pat Kane of Commonweal, who have railed against the bogus civility of the British establishment and argued that a major reset in power relations would create a more humane society. The series that he was commissioned to make for BBC Scotland and which is currently being broadcast, enables McGarvey to present a critique of the powerful from a left-nationalist perspective. To his credit he quickly deleted what were abrasive and threatening tweets and made abject apologies (though not to Campbell personally).

Sturgeon has sought to consolidate her influence through charities and social activist groups as well as prominent social radicals. Their support is guaranteed by different forms of patronage from the state and they may be seen by Sturgeon as more important for her future career than how she is regarded by her own party.

On 22 February Rape Crisis Scotland, overwhelmingly reliant on funding from the Scottish government, called for an emergency summit to decide whether the identity of the complainants against Salmond risked being revealed by his testimony in 48-hours’ time. (This was despite the fact that the material had already been published by the Spectator.) Soon advisers to MSPs at Holyrood weighed in with near identical statements urging that another delay into the parliamentary inquiry occur.

They may well get their wish. Ultimately, unless the inquiry collapses, a very truncated report is likely to emerge that will evade whether Sturgeon gave misleading evidence to parliament, that is after Alex Salmond is prevented from being questioned about matters which a judge has already allowed to be in the public domain. The Crown office headed by a Lord Advocate who combines the twin roles as head of prosecutions and chief government legal adviser, has been involved in frenetic efforts to prevent the inquiry members being able to question Salmond about elements in his legal submission which focus on Sturgeon’s role in the pile-on against him from within the Scottish power structure. James Wolffe, chief prosecutor and a Sturgeon loyalist within the government, seems able to overawe the corporate officers of parliament and force them to retreat from allowing the Salmond submission to be fully considered by the inquiry. Arguably, it is a deformed democracy in which a parliament is able to be thwarted in its search for the truth in the most serious crisis of the modern era in Scottish politics.

Sturgeon has a praetorian guard composed not just of social radicals but of these bureaucratic and legal allies who have staked their careers on her being able to transform the political order into a narrowly personal one. She will know from her husband, the chief executive of the SNP, that several tens of thousands of people have left the party recently and prominent journalists report that the figure has spiked this year. But she probably is happier with being the mistress of a much slimmer vanguard force, knowing that the fatal blow to her career would be unlikely to come from it. Outspoken, egotistical, determined and principled nationalists have sought to make the party’s leadership answerable to a code of conduct but increasingly the party functions like a national social club where their warnings about Sturgeon fall on deaf ears.

In the devolution era the party has greatly benefited from the mistakes of those trying to block the separatist juggernaut as well as the ruthless opportunism of its present leader and her predecessor. Its misfortune is that one of the pair decided to use the blacker arts of politics to try and destroy the other in a gesture as unnecessary as Hitler’s decision to invade the Soviet Union in June 1941.

Sturgeon’s absence of contrition given what she, senior civil-servants and former colleagues of Alex Salmond have put the architect of modern Scottish nationalism through, is breathtaking. It shows a cold-blooded operator with an unquenchable appetite for power the likes of which has arguably not been seen in the past annals of British politics.

Characteristically, she has begun the campaign for the election-lite in May with a provocative gesture straight out of the playbook of demagogues in pre- and post-1945 Europe. Last week, as restrictions on electioneering were revealed, she announced not only would the Union flag continue to be forbidden from flying on Scottish public buildings except for Remembrance Day (this was the existing policy) introduced in 2018 but – in a transparently petty move which shows how bleak and cynical her view of human nature is – she resolved to display in its place on every day of the year the flag of an organization, the European Union, which Scotland no longer belongs to and is most unlikely to be intimately connected with in the future.

Why now, all of a sudden? Another Dead Cat prank?

The European issue is just a convenient wedge issue designed to erect barriers with the rest of the island of Britain and throw red meat to supporters wondering if she is still the real deal. The disinterest in Scotland felt by the EU was shown days beforehand when Ursula von der Leyen made it clear there was no intention of tweaking the rules to allow Scottish students to continue being part of the Erasmus educational programme. Brussels may be ready to risk its reputation by pushing Northern Ireland to the brink of fresh violence through superseding the 1998 peace agreement with a divisive protocol, but it still has enough common sense not to plunge into the morass of Scottish politics.

With media figures so embroiled in the internecine struggles eroding the appeal of the SNP, not least among former supporters, the last place where the eclipse of political nationalism as a ruling project will be aired is in the television studios of London and Scotland. But change is on its way. A large swathe of voters have had the scales lifted from their eyes by the way Sturgeon has mishandled the pandemic.

But it doesn’t mean that the Scottish Conservatives will be the main beneficiary of years of misrule by a semi-despotic figure. All for Unity is on the ballot paper across Scotland: despite a media blackout, its focus on fixing a broken state and ability to place talented professionals on its candidate list means it will stand above the career politicians and likely be a force to be reckoned with beyond May.

Scotland badly needs to stop imitating a banana republic in a cold climate. The excesses of Sturgeonism mean that deliverance could soon be at hand.

If you enjoyed this article please share and follow us on Twitter here – and like and comment on facebook here.

Tom Gallagher is Emeritus Professor of Politics at the University of Bradford. He is the author of Theft of a Nation: Romania Since Communism, Hurst publishers 2005. His latest book is Salazar, the Dictator Who Refused to Die, Hurst Publishers 2020 (available here) and his twitter account is @cultfree54