HAFEZ AL-ASSAD, who ruled Syria from 1970 to 1999, asked a diplomat not long after the overthrow of Ceausescu in 1989: Tell me, how could a man like [Nicolae] Ceausescu, who controlled the security services, the military, all the newspapers and television stations, and the entire political apparatus, be overthrown and executed? How was that possible? I’m only asking because I am curious.

A simple answer as to why he failed to die peacefully in his bed exists. Unlike the autocrat in neighbouring Yugoslavia, Josip Broz Tito who died in 1980, Ceausescu failed to be a ‘good father’ to his people. Like Scotland in times past, the Balkan peninsula had long known patriarchal politics. Land was fought over and different religious and ethnic groups struggled for supremacy, meaning that powerful authority figures were expected to try to ensure cohesion and even survival in hazardous times.

It is a kink of history that a determined effort has been made to introduce this kind of implacable personal rule (albeit in its matriarchal form) when the need for it seems hardly apparent. None of the elements of threat loom on the horizon which confronted Scotland in the distant past.

Nicola Sturgeon’s decision to rule like an autocrat in an increasingly skeletal democracy with shrinking checks and balances, has been very much her own choice. She prefers self-agrandisement and has sought it by picking fights and promoting a dogmatic version of her national ideology, rather than improving living standards, strengthening public infrastructure or tackling social ills like the toll of drug deaths. She has spurned Tito’s model of being a developmental ruler in favour of being the authoritarian Scrooge like Ceausescu who channelled benefits in the direction of himself and his clique.

To the lasting discredit of her party which now has 108 MPs and MSPs, only a small number have stood in her way even as she helped set in motion a series of legal and bureaucratic steps meant to permanently silence Alex Salmond. Ceausescu in his heyday was also determined to ensure that any rivals – living or dead – would not stand in his way of becoming the greatest communist ever seen in Romania. The past was re-written in Romania just as Sturgeon has lost no time in erasing any significant role for her predecessor as leader in the official record of the party’s march to power.

Despite the severe sanctions for dissent, Ceausescu faced occasional challenges such as the one from Constantin Pirvulescu. In 1979, this 84-year-old mounted a plucky challenge to a ruler increasingly divorced from reality. The veteran’s record of militancy put the general secretary’s in the shade. Pirvulescu had served as a volunteer in the Russian Red Army after 1917 and studied in a Soviet revolutionary school for much of the 1920s. His eminence meant he managed to speak at that year’s party congress. On the rostrum he complained it had been organized “solely to re-elect Ceausescu. The major problems of the country have not been discussed.” A video clip exists which shows the initial amazement of the delegates and how it quickly turned to fury when the platform realised – he had gone rogue.

For his defiance Pirvulescu was slung out of his spacious Bucharest apartment and placed under house arrest in a faraway town.

No such challenge to Sturgeon has ever risen at any of the SNP conferences – all we can determine is anxious murmuring about the complaints of her internal critics being swept under the carpet by the party machine, controlled by Sturgeon’s (now) husband these past twenty years. The critic who enjoyed most leeway, at least until 21 January this year was Robin McAlpine, the founder of an influential platform ‘Commonweal’. He is an energetic campaigner and a talented writer. Days before his colleagues on the board of the group asked him to quit, he had accused Sturgeon of being a disastrous influence both on Scotland and the Scottish National Party due to the arbitrary practices that had arisen (or been intensified) in government during her time at the top.

What pressures were put on colleagues to remove him can only be guessed at. But it is likely they were vigorously applied. Numerous broadcasting outlets and newspapers rely very much on government advertising revenue to stay afloat and appearances from him are unlikely even though he turned Commonweal into a strong campaigning tool during the 2014 referendum on independence.

A dummvirate or family compact is in charge of Scotland. With her husband running the party in a not dissimilar way to how the wife of the Romanian dictator was in charge of party affairs, it would seem Nicola Sturgeon is leaving little to chance. But dissent is impossible to quell if power-hungry partners are responsible for terrible mismanagement of the country. A lot of doctors are up-in-arms because her mania for red tape ensures the vaccine drive against Covid-19 is so much slower than in the rest of the UK.

They want to bypass the health boards which are often staffed by SNP appointees, so they can do their job. At least one polls reveals calls for Sturgeon’s resignation enjoy strong support even in the SNP if she is shown to have played a role in the attempt to politically silence her predecessor.

Despite his supposedly iron grip on an apparatus of control, it took a mere nine days of unrest before Ceausescu was toppled in 1989 and permanently removed from the picture. He had overlooked the need to share the benefits of his rule with the rest of the party and had pushed a cold, under-nourished and oppressed people to the limits of their endurance.

His execution brought an end to a 45-year experiment with communism that was unsuited for any country but especially one like Romania where wealth was concentrated in its rich farmlands and forests and abundant waterways.

Like the Scottish Nationalists who, for decades, operated ineffectually on the margins of politics, Romanian communists were fringe politicians in early 1945. The party never had more than 1500 members in the first decades of its existence: one of the lowest proportions in Eastern Europe. But its prospects were transformed when the Soviet Red Army occupied all of Romania at this crucial turning-point in history. The Roosevelt administration’s naivete about Stalin enabled 87 million inhabitants in East-Central Europe to fall under Soviet domination. Romania was swallowed up in the new Soviet empire and its politics were quickly transformed out of all recognition.

It is not hard to imagine the same grim scenario unfolding if Britain’s solitary resistance against Hitler and the Nazis in 1940-41 had ended in defeat and occupation. Leading figures in the SNP like Arthur Donaldson and Douglas Young had few scruples about Scotland falling under German control as long as its continental occupiers ensured an important degree of separation from the rest of the British island

The tides of war ensured the SNP did not enjoy the astounding fortune of the Romanian communists. They were ironically placed in power by the army of a country which, under the Tsars and Lenin’s Bolsheviks, had been an avowed enemy of Romanian independence. With a docile regime installed in Bucharest, Stalin assumed that Romania’s ability to be a pro-western salient in the Balkans had been ended, perhaps forever. But unlike the Labour social democrats of the Blair era who assumed that “devolution will kill Nationalism stone dead”, the Muscovites holding Romania captive were not complacent. A ferocious attack was launched against all institutions and individuals seen as representing a threat to the new order. Class enemies were imprisoned in their tens of thousands and stripped of their wealth.

Nicola Sturgeon has similar class enemies to the pre-1989 communists but she has moved against them at an incremental pace. The curbs on private schools and on age-old landowning practices in the Highlands have been her preferred means along with restrictions on forms of speech which not even the Romanian communists had dreamt up.

The architect of Romanian communism, Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej was one of the few working-class ethnic Romanians to be found in a party initially dominated by intellectuals and ethnic minorities. He quickly started a recruitment drive among some of the most hard-headed peasants who were used to force through the collectivisation of the economy and crush dissent. Dej had character traits that might evoke parallels with Alex Salmond – but not Salmond’s successor. He was gregarious, ebullient and enjoyed many of the good things of life.

Having grown up in Jewish communities, he had a vast repertoire of Jewish jokes. As Ceausescu ascended the party hierarchy, his boss would occasionally do a hilarious take-off of his walk, mannerisms and stutter.

The death of Stalin in 1953 posed problems for the leaders of satellite parties like Romania’s which had a bloody record of repression. His eventual successor Nikita Khrushchev wished to place less tarnished figures in charge of the ‘Peoples Democracies’.

Dej decided to resist and declare communist Romania independent of Moscow. He was going to pursue a nationally-orientated form of Stalinism to protect his regime against Soviet meddling. This was quite a turn-around for a regime which had hitherto been busy removing the national idea from education and culture. But plans for going-it-alone were pursued surreptitiously so as not to arouse Moscow’s suspicion.

Dej would perhaps have been surprised by the non-stop posture of confrontation with London pursued by the SNP’s two First Ministers from 2007. He might even have wondered if their level of overt aggression against the lynch-pin of British power was simply play-acting and that these nationalists were ultimately UN-serious about independence.

The wily communist boss ingratiated himself with the Soviets by helping to crush the Hungarian revolution of 1956. He handed Imry Nagy, who had assumed the leadership of the rebellion, over to the Soviets after he had taken refuge in Romania. There was enough proof of loyalty for the Soviets to be talked into withdrawing all their forces from Romanian soil by 1958.

Three years later Dej surprised many in the West by lining up with China when the communist bloc was split thanks to the quarrel between its Mao and Kruschev. He also defied Khrushchev’s call for Romania to remain the bread-basket of the Soviet bloc and instead pursued a strategy of rapid industrialisation. Western know-how would be needed and Romania started to pursue an independent-looking foreign policy.

A country in the throes of rapid economic change, using nationalism as a tool to strengthen its hold over the masses, and gingerly extending feelers to the West, was the one Nicolae Ceausescu inherited in 1965 when Dej died unexpectedly and quickly from a rapidly spreading lung cancer.

Party elders thought that the dour and intense Ceausescu who had risen through the ranks, would be easy to keep in check. But within a short time, they were to get a shock, perhaps as big as the one confronting Alex Salmond when faced with the appalling evidence in 2018 that Nicola Sturgeon was not turning out as he had hoped she would.

Once Romanians realised how much of a martinet their leader was, dissidents like Paul Goma were heard to say: “We Romanians live under Romanian occupation – ultimately more painful, more efficient than a foreign occupation.”

It is still an exaggeration to say that Scots are living under a Scottish occupation. But for how much longer will that be the case?

With Sturgeon’s non-stop effort to boost her image abroad kept in mind, the next part, will examine how Ceausescu’s need for international glory consolidated his rule only to sow the seeds of his ultimate downfall.

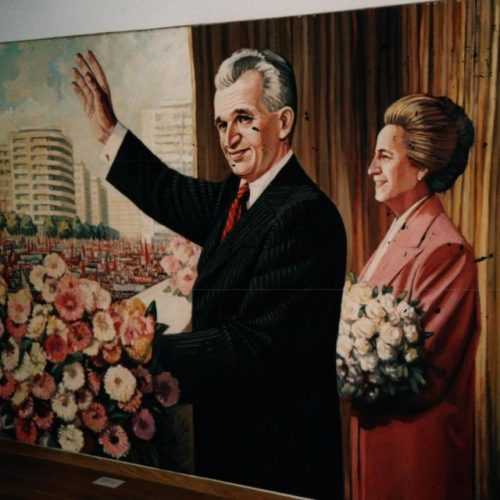

The main photo at the top of the article is a portrait of the ruling Romanian couple waving to the masses. The others were taken in the Romanian cities of Cluj and Braila in the early 1990s when, except for the onset of a free press and semi-free elections, the arrival of genuine change was very slow indeed.